FREAKOPHONE WORLD

(Inside the Castle, 2021)

FREAKOPHONE WORLD performs both as a book-length poem and occulted terrain, which together reimagines black diasporic life in an increasingly imperiled and globalized society. The speaker in this poem comes from a long tradition—of FREAKS, outsiders, others, and spirits calling out to the living reader from the undead, black, and unapologetically freakophonic space of the text.

ISBN: 978-1-7352901-4-0

Reviews:

Tarpaulin Sky | "Madison McCartha's Freakophone World," Reviewed by Olivia Cronk and Philip Sorenson

Advanced Praise

The FREAKOPHONE WORLD is up under ours, down cavernous tracts that are mouths, bowels, and tombs. Thus, with this immersive phantasmagoria Madison McCartha is not quite speculating a future, rather enfleshing the grotesque present, the slow-grinding decay that is living. McCartha’s assured, inventive, irradiated voice renders the speaker a chimera of grievance, sensuality, insight, and orneriness chucking the shit-talk of those who’ve been below long enough to know what’s been sown, where everything is buried.

—Douglas Kearney, author of Sho

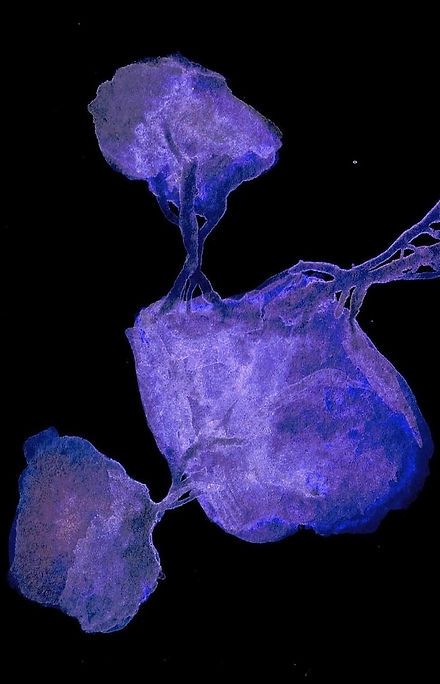

A marvel of continuous lyric transformation, FREAKOPHONE WORLD, Madison McCartha’s debut collection, explodes like the aftermath of a funky Big Bang, bringing a wild, libidinously queer world into view. A dizzying freakologic tour as much as a tour de force of imagination, language, and design, McCartha’s vision includes their original paintings, which prove integral to the freakaphonic constellations herein.

—John Keene, MacArthur winning author of Counternarratives

Like a spider web, the FREAKOPHONE WORLD is a sub-detectible version of our own— sub-detectible, that is, until it's right in our face—and then it is our face. Madison McCartha's debut volume serves as a svelte, arachnoid landing site for their multimodal project of presencing the katabatic, freakophone web whose filaments we tremble as we shiver, sleep and shake.

—Joyelle McSweeney, author of Toxicon and Arachne

Madison McCartha has the unique talent of converting each word they use into a spectral, zygotic megaphone (our many voices rising like resin) that amplifies the rare science, rare medium of their biotic rumination. Their embryonic, post-watercolored art laced with the lexical, zany treatment of rectum, reticulum, septum, (also ambergris, needle, ‘alloyed genitals’) and sole chromaflock are all rawboned almonds in a posthuman us waiting to be reborn into the hemline, oceanbrine, concupiscent, demon-fecund, lanky distance which they call FREAKOPHONE.

–VI KHI NAO, author of The Vegas Dilemma

”The kinetic sorcery of Madison McCartha’s FREAKOPHONE WORLD is vested in the kaleidoscopic potential that it gathers, holds, and ultimately releases in newly made arrangements. Think of this potential as an incision— a honed wound that reveals layer upon layer of logic. The logic is steadfast but mutable, and it continuously orders and reorders itself. Infinite trials of how-can-we-be enter the frame. Through the viscous words and images inside this collection, McCartha presents a series of punctuated, percussive replies to the initial how-can-we-be. The replies can be set side-by-side just long enough for their discrete components to exist in the same frame— then they find their rightful movement alongside new peripheries. In the paintings inside FREAKOPHONE WORLD, there are moments where we enter a whole wilderness of longing, where McCartha invites us to reconsider the empirical limits of scale, scope and containment. FREAKOPHONE WORLD lays bare the endless electric entanglements that exist. McCartha guides the reader to them, precisely aligning the frame before shifting it again.”

–Asiya Wadud, author of No Knowledge Is Complete Until It Passes Through My Body

Kinetic Footage from The FREAKO-PHONE WORLD

the Kinetic Footage:

Before the footage and the paintings, I was thinking about House music as a poetics of ongoingness, of an inter-cutting movement, and the space it invokes; an expansive space both contiguous and in tension with what Simone White calls “the methodology of surround” found in trap music: an encompassing soundscape which refracts, enacts and commodifies black suffering: a club “we find ourselves in” says White, “that we have not chosen to enter”: a world-space which theorist Édouard Glissant might call an echo-monde—"the ante-club, everywhere." The space of the club became an important model with which to think about space in these video-poems; important, because it brings up Detroit, to my mind, as an origin point both for House music, and for my own personal history and relationship with music. I was born in Detroit, and House was the music my father listened to. The music I grew up with.

Before these videos began, I knew I wanted to attempt a text animation that would give the viewer the sensation of moving or being moved around inside the poem—in the dark. Early on in my MFA workshops at the University of Notre Dame, a professor (Joyelle McSweeney) had said to me, about writer Amos Tutuola, that his language seemed "to come out of the dark"—which hit a chord, resonated, and spoke back to Ann Waldman's poem, "Painting Makeup on Empty Space," which arrives on the page "from nothing" (as Waldman puts it), or from nowhere; an arrival of which any dynamic, surprising poem might be capable.

I also wanted this space, in these kinetic films, to be in tension with its occupying bodies. Besides the digital text, the many land- and word-scapes were painted freehand with watercolor and wax on cardstock, and then digitally altered. These bodies became a means of expressing a double-difference (a difference among the different) and a way, by accident, of re-encountering myself not just as a poet, but as a visual artist. While their individual movements and font-shapes felt more intuitive, I think the most personal and (in my view) political choice was to give them their color.

While at The Millay Colony in August of 2018, a few other residents and I drove out to MassMoCA (The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art), which was holding an exhibit titled Lure of the Dark. I was struck, there, by the near-glowing paintings of Afro-Caribbean artist Cy Gavin, whose color palettes were bright, florid—even 'loud'. What was happening, there, was that the dimly lit exhibition-space had forced a shift in the spectrum of available light as it hit the paint, making Gavin's landscapes feel otherworldly, irradiated, or like something glimpsed in infra-red.

The exhibit clicked with another resident, a friend, who works in fabric 'paintings' (he calls them), work that queers the grid, and in colors that seem to come out of the dark. He was reading Chromaphobia at the time, a book that talks about color as a sign of excess and otherness, of the illegitimate; but also as something often "close to the body and never far from sexuality," or, to echo Derek Jarman, as something with "a Queer bent." In these video-poems also, vibrancies of color and vibrancies of affect start to function as a kind of queer subversion; a subversive response to (and expression of) violence. Because when color arises as a response to violence, the violenced body creates a non-obliterative subversion, where the violence isn't erased or forgotten, but is instead transmuted into another kind of intensity.

Back at the residency, thinking of Cy Gavin, I started looking through two photobooks brought from home; each book had stills from the video installations of Swedish artist Nathalie Djurberg. I’m interested in how vibrancy takes shape in Djurberg's stop-motion films, as something that spills from the interior—to breaks its world. When a black plasticine woman is tortured to death, or when a clay black man, maybe a black factory worker, in his gingerbread colored uniform is tenderly flattened with a rolling-pin until he too starts to spill, what is that blue-green ooze leaking instead of blood? That clay material—that is, the material of the world-space itself—excreting from his neck, eyes and feet? What is this violent-affect-fluid? Can this vibrancy be held, or even reclaimed as a similar response to violence?

The textural illegibility of Djurberg's clay means everything to me—and in a few still images from Djurberg's stop-motion film, The Clearing The Winner, that material arrives as language. Its near-neon text twisted from clay--whose color is its light—suspended in its nowhere. I'm interested in this formal multiplicity, this straddling between media, and the ways the clay imperfectly occupies (and abjects, to use Kristeva’s language) these textual bodies. In my video-poems, these ‘kinetic films’, I'm thinking back to poet Ken Chen's essay on sublime trauma, about the "gargantuan terror of colonialism, that distorts our mouths as we speak it", and the ways that somehow the poem's intensities of affect (of being) cannot be fully rendered visually, and even when arriving as language, that the language itself, as a material object, must stretch and distort to hold those affects—if held at all.